Yesterday before they landed

in our history

of roots recited

of origins memorised

who you were exactly

what your place was

in the world of our people

It’s up to you, my mother,

it’s up to you, my sister

to try and find out….

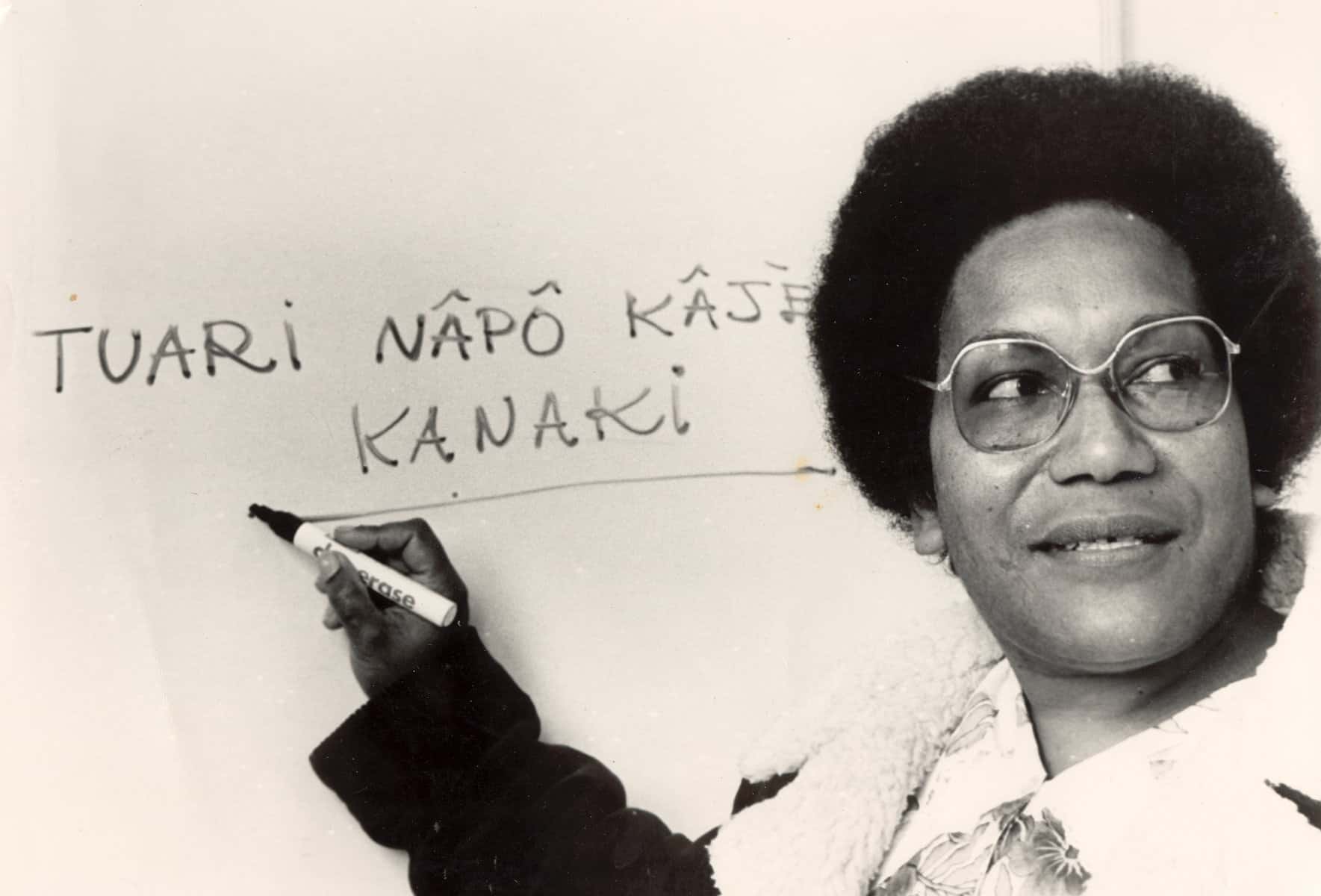

“Millenia”, written in Camp Est prison in 1974 by Déwé Gorodé

One of the great champions of Oceanic culture has left us. Poet, teacher, feminist and politician, Déwé Gorodé was a beacon for women’s rights and self-determination and a leader of the Front de Liberation Nationale Kanak et Socialiste (FLNKS) in the French territory of New Caledonia. Her death on 14 August, aged 73, ended a life of courage as an advocate for the rights of indigenous people and the status of women across the region.

Born on 1 June 1949, Eperi Déwé Gorodé grew up in the Kanak tribe Tribu de l’Embouchure, near the east coast town of Ponerihouen on New Caledonia’s main island. Educated in Houaïlou and the capital Nouméa, Déwé travelled to France in the early 1970s and was one of the first Kanak women to study at university, gaining a degree in literature from Montpellier in 1973.

Her political awakening came during these turbulent years, when there were many influences for a young indigenous woman: the Aboriginal land rights movement in Australia and black power in the United States; protests against the Vietnam War; the writings of négritude authors like Aimé Césaire; the aftermath of the May 1968 student and worker protests in France; and burgeoning anti-nuclear protests and self-determination struggles across the South Pacific.

In an interview, she noted: “Student life was in turmoil after May ‘68. Every type of Marxist group – communist, Trotskyist, gauchiste – were handing out leaflets, there were protests, meetings, demonstrations, debate, strikes. It was a time of anti-colonialism, though French people know nothing of my islands. But it was this time that helped set me on the path of political action, working for my people as a writer, a teacher and a member of the Kanak independence movement.”

On her return to New Caledonia, she joined the radical youth movement Foulards Rouges (Red Scarves), protesting alongside Nidoish Naisseline, Paul Neaoutyine and other young militants. In 1974, Gorodé co-founded the Groupe 1878 (an allusion to the 1878 Kanak rebellion by Chief Atai). Two years later, she co-founded the Parti de Libération Kanak (Palika), which continues today as one of New Caledonia’s major political parties.

Conflict in New Caledonia

In the mid-1980s, New Caledonia was racked by violent clashes between the independence movement, extremist settlers and the French Army. Déwé was one of many women who came to the fore in this period, stressing the importance of women’s rights in the independence struggle but also in any future nation. As a teacher and activist, a poet and intellectual, Déwé was outspoken in the early days of the Kanak independence movement – a role model for many young people who deferred to their elders in Kanak custom.

In September 1974, Déwé Gorodé and Susanna Ounei were arrested for protesting against ceremonies that commemorated the colonisation of New Caledonia on 24 September 1853. It was the first of three stints in jail in 1974-77, and in prison she wrote poetry and joined other young people to reflect on the role of women in the independence movement. Together with Susanna Ounei, she was one of the founders of the small feminist network Groupe de femmes kanak exploitées en lutte (GFKEL – the Group of Kanak and Exploited Women in Struggle). GFKEL in turn was one of the founding organisations of the FLNKS – the coalition of independence parties and social movements created in September 1984.

She abhorred violence against women, but as a Kanak nationalist, she also challenged the intersection of this plague in the context of French colonisation and also patriarchal values in Kanak custom.

In a 1994 interview with Susanna Ounei, she reflected on women’s role in Melanesian society: “Despite our roles, there are certain places or certain powers where we women have no access. I refer, for example, to public speeches, the public announcement of the alliance of the clans, the genealogical discourse. We have no access to this because it is the man who makes such speeches in public. An example is la grande case, the big hut where all the important decisions of the clan are made, which belongs to the men. True, the men built that hut, but if they can go in there and speak in the name of their clan, to the glory of their clan, to recount the prestige of their clan, they have to acknowledge our role of enlarging the clan, making alliances so that the clan can expand.”

Beyond her own country, Déwé supported the movement for a Nuclear Free and Independent Pacific (NFIP), speaking out against nuclear testing and in support of independence movements in the Pacific. As a young woman, she attended the 1978 NFIP meeting of independence movements in Pohnpei – fellow participants included activists who became leading figures in Pacific politics, culture and development (independence campaigner Oscar Temaru from Maohi Nui / French Polynesia; Aboriginal writer and activist Gary Foley; politician, writer and promoter of the “Melanesian Way“ Bernard Narokobi of Papua New Guinea; and Father Walter Lini, the first Prime Minister of Vanuatu after 1980).

Education and poetry

When we first met in 1985, she had left the formal education system to become a leading figure in the Ecoles Populaires Kanak (EPK) movement, creating Kanak community schools to teach indigenous children about their history, culture and languages.

That year, after an FLNKS congress at Hienghène, French paramilitary police blocked our passage back to the capital Noumea. We were told to obey the curfew, turned around, and sent back the way we’d come. Taken in by local villagers, I sat that night with Déwé, Gabriel Monteapo and other Kanak activists – talking by firelight about the role of education as a force for liberation. Seen as radical at the time, many of the EPK principles have now been integrated into New Caledonia’s education system – such as the use of vernacular languages in primary education, and the importance of new historiography that places New Caledonia in its regional environment.

Throughout this era of armed conflict, she retained her love of literature, publishing her first book of poetry Sous les cendres des conques in 1985. I have vivid memories of visiting her home in the village as she studied to upgrade her teaching degree, reading Tristan and Isolde by the light of a lantern. The independence movement sparked a renaissance of Kanak language, dance, music and art and Déwé was a leading figure in this cultural revival. Over the years, her prodigious output of poetry, short stories, novels and theatre was a beacon of Oceanic literature (for English speakers, some of her early poetry and short stories are collected as “The Kanak Apple Season”, and “Sharing as custom provides”, published by ANU Pandanus Press).

Writing in French, English and her own language Païci, she was prolific throughout the 1990s, with collections of short stories – Utê Mûrûnûu (1994), L’Agenda (1996) and Le Vol de la Parole (2002) – and several more volumes of poetry, including Par les temps qui courent (1996), Pierre noire (1997) and Dire le vrai (1999). Later, she turned to novels such as L’épave, Graines de pin colonnaire and Tâdo, tâdo, wéé!

Lauded across France and the Pacific as an indigenous and feminist writer, she always directed her work towards the new generation building an independent Kanaky New Caledonia: “I don’t write for myself. I write for the children, for the generations to come. I pass on my experience, my vision, in many ways. Writing is obviously important, but I talk a lot to the young women in my family, my nieces and their friends. I continue to talk to the young, for the younger generation is our future.”

Politician for common destiny

After the adoption of the Noumea Accord in May 1998, New Caledonia was served by new political institutions, including three provincial assemblies, a national Congress and multi-party, collegial government. Elected to Congress in May 1999, Déwé and Léonie Varnier were the first women in the new legislature. As a member from the Northern Province, she was then re-elected several times for the Union nationale pour l’indépendance (UNI) parliamentary group.

In 1999, she joined the first post-Noumea Accord government under President Jean Lèques, as minister for Culture, Youth and Sports. Between April 2001 and June 2009, she was elected as Vice President of the government under successive anti-independence Presidents Pierre Frogier, Marie-Noëlle Thémereau and Harold Martin (between 2004-07, President Thémereau and Vice-President Gorode were the first two women elected to lead a government in the Pacific islands, a precursor of the rising generation of female Presidents and Prime Ministers who serve across the region today).

Dogged by ill health, she continued as a minister for citizenship and women, seeking to the post-conflict reconciliation required to create a “common destiny” for the French dependency. Through her focus on citizenship, the one-time firebrand sought to forge a common bond between indigenous Kanaks and the “victims of history” – the descendants of French convicts, indentured labourers and settlers born in New Caledonia, and immigrants from other French colonies (such as Wallis and Futuna) who have made New Caledonia their home.

She is survived by daughter Leila and son Albert, after the death of her husband Marcel Pouroin and young son Marc.

Ake, ake, ake.